Several species of grouse inhabit my backyard (Wrangell/St. Elias National Park and Preserve), Alaska. Above, sharp-tailed grouse.

video link below: Grouse in my backyard

Several species of grouse inhabit my backyard (Wrangell/St. Elias National Park and Preserve), Alaska. Above, sharp-tailed grouse.

video link below: Grouse in my backyard

Check out my owl photos in June/July 2025 RANGER RICK by clicking link below.

Unlike most species of gulls, Bonapart’s gulls nest in trees.

Unlike most species of gulls, Bonapart’s gulls nest in trees.

Baby Bonapart’s gulls stayed in the nest for a day before jumping out and heading for nearby boreal ponds.

The aggressive and noisy Bonaparte’s gulls emit ear-splitting screams and drop hot, slimy poop bombs as they drive away enemies from their eggs and young, leaving enemies from ravens to eagles to nosy photographers diving for cover.

Bonaparte’s gull attacks!

To view video of Bonaparte’s gull click the link below.

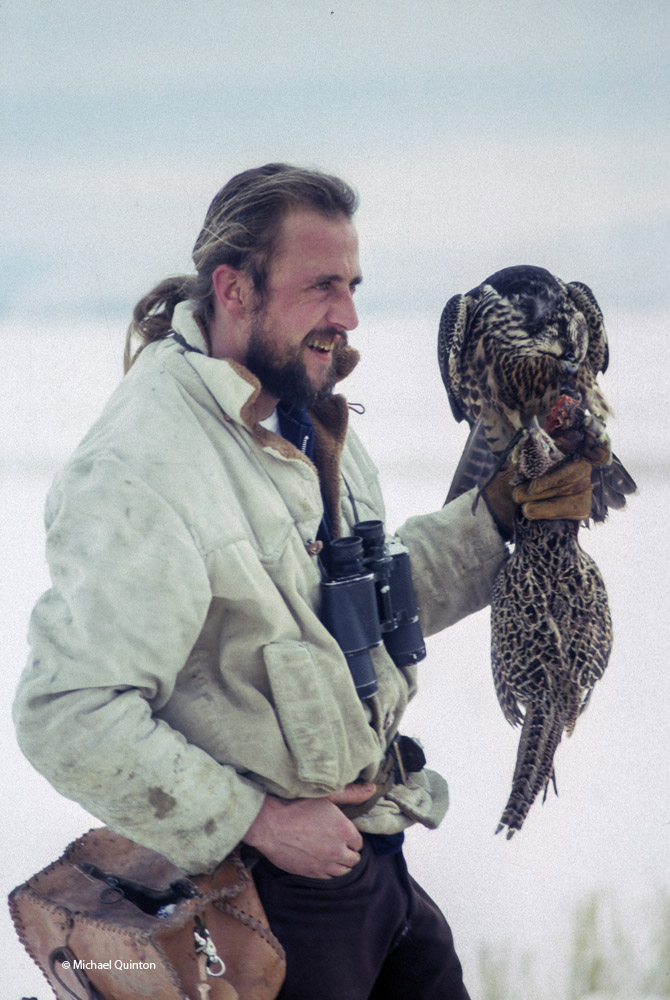

I couldn’t help but notice two hooded falcons perched on the back seat of a VW bug in the grocery store parking lot where I worked. ( forty-five years ago!) A guy with a ponytail drove it. When I said something about the prairie falcons, he looked a bit surprised. I guess nobody had ever correctly identified his falcons before. That’s how I first met Terry Heath. And with that introduction, we shared a short conservation that ended with Terry inviting me to photograph his hunting falcons. As I tagged along on hunting trips It became clear that for Terry, falconry was no hobby, nor was it just a sport hunting venture. No, Terry was in the grip of a full-blown obsession with falcons.

I couldn’t help but notice two hooded falcons perched on the back seat of a VW bug in the grocery store parking lot where I worked. ( forty-five years ago!) A guy with a ponytail drove it. When I said something about the prairie falcons, he looked a bit surprised. I guess nobody had ever correctly identified his falcons before. That’s how I first met Terry Heath. And with that introduction, we shared a short conservation that ended with Terry inviting me to photograph his hunting falcons. As I tagged along on hunting trips It became clear that for Terry, falconry was no hobby, nor was it just a sport hunting venture. No, Terry was in the grip of a full-blown obsession with falcons.

THE PRAIRIE FALCON

Week-old prairie falcons huddle together on a simple scrape at their cliff eyrie. The aggressive divebombing adults give Terry a glimpse into the potential flight characteristics of the young falcons.

Week-old prairie falcons huddle together on a simple scrape at their cliff eyrie. The aggressive divebombing adults give Terry a glimpse into the potential flight characteristics of the young falcons.

Early in her training, (above) the young female prairie falcon is content to sit on the sidelines and let Terry demonstrate. From such modest beginnings, the prairie quickly responds to training and will be introduced to wild pheasants and ducks soon. (below)

Early in her training, (above) the young female prairie falcon is content to sit on the sidelines and let Terry demonstrate. From such modest beginnings, the prairie quickly responds to training and will be introduced to wild pheasants and ducks soon. (below)

Casting off…

Casting off…

A PEREGRINE NAMED ANGEL

Another mallard for the bag. Every flight of Angel, the peregrine, was stunning,

Another mallard for the bag. Every flight of Angel, the peregrine, was stunning,

Angel suddenly reappears out of nowhere to stoop on the lure. (above) For a few worrying minutes, Angel was nowhere to be seen. Had she made a kill out of sight? A big worry.

Angel suddenly reappears out of nowhere to stoop on the lure. (above) For a few worrying minutes, Angel was nowhere to be seen. Had she made a kill out of sight? A big worry.  A falcon with a full crop is difficult to coax to the glove. Candy (right) was a fixture on the hunting trips. But once, after hawking for pheasants, Candy went missing and didn’t return to the car. Before leaving Terry threw out his coat. The next morning there she lay, waiting.

A falcon with a full crop is difficult to coax to the glove. Candy (right) was a fixture on the hunting trips. But once, after hawking for pheasants, Candy went missing and didn’t return to the car. Before leaving Terry threw out his coat. The next morning there she lay, waiting.

Searching for suitable quarry for the falcons led us out to the edge of the lava flows of eastern Idaho. Passing a pair of ravens hanging out along the road, Terry slows and pulls over a couple of hundred yards down the road. Stepping out of the van Terry removes the peregrines hood and lifts the falcon above his head. In an instant, the peregrine is off the glove and power-pumping those long, slender wings into the wind towards the dumb-struck ravens. From a jump start, the ravens took flight and started to climb. Now, these ravens share the sky with all kinds of raptors from goshawks to golden eagles so the sudden appearance of a peregrine is no big deal. But this one had them in the crosshairs! Though the peregrine’s power of flight is legendary, she could not outclimb the ravens. A peregrines advantage is on the way back down and the ravens knew it. The flight was quickly a quarter mile above the sage highlands and climbing. But the persistent peregrine wouldn’t give up. As the flight threatened to disappear, out came the lure.

Searching for suitable quarry for the falcons led us out to the edge of the lava flows of eastern Idaho. Passing a pair of ravens hanging out along the road, Terry slows and pulls over a couple of hundred yards down the road. Stepping out of the van Terry removes the peregrines hood and lifts the falcon above his head. In an instant, the peregrine is off the glove and power-pumping those long, slender wings into the wind towards the dumb-struck ravens. From a jump start, the ravens took flight and started to climb. Now, these ravens share the sky with all kinds of raptors from goshawks to golden eagles so the sudden appearance of a peregrine is no big deal. But this one had them in the crosshairs! Though the peregrine’s power of flight is legendary, she could not outclimb the ravens. A peregrines advantage is on the way back down and the ravens knew it. The flight was quickly a quarter mile above the sage highlands and climbing. But the persistent peregrine wouldn’t give up. As the flight threatened to disappear, out came the lure.

Desperate to get back to open water, the mallard deploys futile last-second maneuvers. The peregrines focus is clear. Mine, not so much.

Desperate to get back to open water, the mallard deploys futile last-second maneuvers. The peregrines focus is clear. Mine, not so much.

Wary of leaving the security of the Slana River, an adult beaver slowly approaches a scent mound. Interrupting an invisible beam, the beaver triggers a digital camera to capture this self portrait.

BEAVER BEHAVIOR

Hauling armloads of mud and moss, beavers continually add to their mounds and frequently add a fresh scent. Bulletin boards for beavers, scent mounds are important features of their territory. And a good place to set up a camera trap I thought. You know, just to see what might pass. Kind of a wildlife selfie station. I pick the place, they pick the time.

Hauling armloads of mud and moss, beavers continually add to their mounds and frequently add a fresh scent. Bulletin boards for beavers, scent mounds are important features of their territory. And a good place to set up a camera trap I thought. You know, just to see what might pass. Kind of a wildlife selfie station. I pick the place, they pick the time.

Once or twice a month this wandering lynx passed the lens.

Over the spring/summer months the camera had several views of this scent mound. To the beavers the camera was part of the scenery. I had nightmares of them chewing on the camera or even pulling the whole camtraption into the river. But they completely ignored it. Beavers sometimes used the mound as a feeding platform or to just sit and chill for a few minutes. A late night surprise, the south end of a northbound grizzly. (below)

After a couple weeks of rainy weather I arrive at the camera station with a dry Nikon. The set-up is prone to problems. False triggers, battery failure, flash and sensor failure due to moisture, even snowshoe hares chewing cords. The beavers were busy refurbishing an old bare-bones lodge downstream and had all but stopped coming to the scent mound. But I kept the camera station operating. I like unexpected surprises.

After a couple weeks of rainy weather I arrive at the camera station with a dry Nikon. The set-up is prone to problems. False triggers, battery failure, flash and sensor failure due to moisture, even snowshoe hares chewing cords. The beavers were busy refurbishing an old bare-bones lodge downstream and had all but stopped coming to the scent mound. But I kept the camera station operating. I like unexpected surprises.

Dolly varden thrive in the extremely harsh habitat of small creeks throughout interior Alaska. Shy at first, my big remote control underwater camera became just another moss covered rock to the big group of dolly’s. For days I snapped away, testing and re-testing different combinations of lens, focus and exposure.

But for kids checking out the fishing hole, they just know dolly’s are fun and exciting to catch. So take it from this old photographer who refused to grow up, dolly’s aren’t just for girls, they are for kids of all ages.

For two weeks I’d waited along this frozen river in the hopes of photographing the semi-annual caribou migration. Altogether I saw about two hundred caribou, a mere trickle compared to some years. One large group (above) had close to one hundred fifty caribou and the remaining stragglers were in pairs or small groups. The bulk had passed to the west of here earlier.

For two weeks I’d waited along this frozen river in the hopes of photographing the semi-annual caribou migration. Altogether I saw about two hundred caribou, a mere trickle compared to some years. One large group (above) had close to one hundred fifty caribou and the remaining stragglers were in pairs or small groups. The bulk had passed to the west of here earlier.

I knew from past migrations that the freezing rivers naturally funnel the caribou to this big bend in the Copper River Basin. The river, frozen on both sides, was still open in most places down the middle. I had located four likely places on the big bend where caribou had crossed, places with enough cover for a photo ambush. I moved between my ambush points to stay warm and pack down the trail between them so I could quickly move from one to another. On most days I saw no caribou. Though painfully slow, action could come at any moment.

I knew from past migrations that the freezing rivers naturally funnel the caribou to this big bend in the Copper River Basin. The river, frozen on both sides, was still open in most places down the middle. I had located four likely places on the big bend where caribou had crossed, places with enough cover for a photo ambush. I moved between my ambush points to stay warm and pack down the trail between them so I could quickly move from one to another. On most days I saw no caribou. Though painfully slow, action could come at any moment.

And when caribou are suddenly bearing down on my hide, I start forgetting things. Things like warm cabin and cold feet. And exactly, what is it I’m supposed to be doing with the camera? Luckily symptoms of buck fever are temporary.

Of course more often than not the caribou would decide to cross where I wasn’t. With tripod and camera over my shoulder I hurried down my trail trying to stay in camera range. Out of time and breath, I planted the tripod like a mono-pod into the snow and clicked away as they plunged in and swam across.

Of course more often than not the caribou would decide to cross where I wasn’t. With tripod and camera over my shoulder I hurried down my trail trying to stay in camera range. Out of time and breath, I planted the tripod like a mono-pod into the snow and clicked away as they plunged in and swam across.

When I first noticed the caribou calf, it was in the river being carried past me by the current. He managed to climb onto an ice island in the middle of the river. After a couple of minutes he struggled to stand. Even though exhausted, the six month old calf, separated from his mom and in maximum migration mode, was pressed by the urge to keep going. Walking to the edge of the ice he stepped in with a plop and swam across the ten feet of open water but did not attempt to climb out. Instead he turned back to the island, climbed out, laid down and curled up. I stayed hidden knowing if he saw me now he might panic. The calf was in trouble and travel would wait. A rest and recharge now could only help tip the balance in his favor. Half an hour later the six month-old calf was still asleep on the ice. As I slowly moved away and headed home, I had a hunch this young caribou was a survivor.

A pair of gray jays have finished their nest by early April.

A pair of gray jays have finished their nest by early April.

I first saw the gray jays as they flew across the road in front of me. They both carried loads of building materials in their bills. The next day I went searching for their nest. It was rather easy to find as they were both busy with construction. The nest was about twenty feet high in a medium-sized black spruce. They had completed a loose bowl of dry spruce twigs and were currently engaged with stuffing this framework with insulation. The pair gathered black, grizzly hair lichens as well as spruce grouse feathers. But their most prized finds were the long soft plumes of the northern hawk owl. After delivering a load of insulation, the birds would hop into the nest and push with bills and feet as they rotated around in the nest, fitting and forming it to just the right shape. The female begins sitting on the nest and a week later her clutch of spotted eggs is complete. The pair is quiet at the nest site and does not attract attention of those nest raiders, magpies and ravens. When a red squirrel was spotted nearby it was dive-bombed by the male gray jay and driven away.

The female begins sitting on the nest and a week later her clutch of spotted eggs is complete. The pair is quiet at the nest site and does not attract attention of those nest raiders, magpies and ravens. When a red squirrel was spotted nearby it was dive-bombed by the male gray jay and driven away.

For nearly three weeks the female incubated her four eggs. A few times a day she will leave the nest but only for a few minutes, perhaps to drink.

For nearly three weeks the female incubated her four eggs. A few times a day she will leave the nest but only for a few minutes, perhaps to drink.

The male gray jay shows up at the nest about once an hour or so to feed his mate.

The male gray jay shows up at the nest about once an hour or so to feed his mate.

Laying eggs is an energy drain and the female spends hours sleeping.

Laying eggs is an energy drain and the female spends hours sleeping.

Early nesting grays jays must be able to handle cold, wet conditions in their Alaskan habitat.

Early nesting grays jays must be able to handle cold, wet conditions in their Alaskan habitat.

Both adults help feed the quickly growing gray jay chicks. Gray jays store amazing amounts of food including carrion and I wondered if they would feed their cached supplies to their chicks. But Instead they foraged the ground for insects and larva, much better food for the new chicks.

Both adults help feed the quickly growing gray jay chicks. Gray jays store amazing amounts of food including carrion and I wondered if they would feed their cached supplies to their chicks. But Instead they foraged the ground for insects and larva, much better food for the new chicks.

As the chicks grew the gray jays cached stores of carrion became more important. And it quickly became apparent that the nest would never hold four growing chicks for long. By the time the chicks were about two weeks old, they jostle for the best position at the nest. I witnessed deliberate attempts by the larger chicks to force their smaller siblings out. One morning there were just two chicks left in the nest. Below the nest on the ground were the missing chicks, both dead. From human eyes, a tragic event. But for nature, another one of those mysteries of survival.

As the chicks grew the gray jays cached stores of carrion became more important. And it quickly became apparent that the nest would never hold four growing chicks for long. By the time the chicks were about two weeks old, they jostle for the best position at the nest. I witnessed deliberate attempts by the larger chicks to force their smaller siblings out. One morning there were just two chicks left in the nest. Below the nest on the ground were the missing chicks, both dead. From human eyes, a tragic event. But for nature, another one of those mysteries of survival.

Come July of this year the name of the gray jay will change once again. They will officially be known as the Canada jay. And like camp robber and whiskey jack, gray jay will be just another nickname used to describe this gray-colored jay of the northern forests.

A marten pokes up through the snow to look around.

A marten pokes up through the snow to look around.

The shy and careful weasel, not liking to be exposed, has pulled its prey, a snowshoe hare, into deep snow.

The shy and careful weasel, not liking to be exposed, has pulled its prey, a snowshoe hare, into deep snow.

Though I have gone several years between marten sightings in the past, i typically have one or two sightings a year. But, just last week we had a marten hanging out at our place for several days. The forest around our home was laced with its familiar tracks and all the trails seemed to begin at a big wood pile like spokes of a wheel. We saw it several times daily and I was able to take hundreds of photographs of the usually elusive predator. From our front row seat at the window, we watched as the marten climbed up a spruce to a red squirrel nest and stole goodies the squirrel had stashed there. And, once I watched as it chased a snowshoe hare through the black spruce. It managed an amazing burst of speed and very nearly caught up to the hare. But when pressed the hare showed he is even quicker So, I was a bit surprised to look out the window and see the marten tugging and pulling at a hare it had caught during the night. It pulled the hare into the deep snow where it could butcher its prey concealed from the prying eyes of other predator and scavengers. First the marten gnawed off the hares head and cached it in the wood pile. The next day it cached the hares front legs. Cindy and I watched as the solitary marten entertained itself by running an obstacle course around and through the wood pile then roll on its back in the snow.

Though I have gone several years between marten sightings in the past, i typically have one or two sightings a year. But, just last week we had a marten hanging out at our place for several days. The forest around our home was laced with its familiar tracks and all the trails seemed to begin at a big wood pile like spokes of a wheel. We saw it several times daily and I was able to take hundreds of photographs of the usually elusive predator. From our front row seat at the window, we watched as the marten climbed up a spruce to a red squirrel nest and stole goodies the squirrel had stashed there. And, once I watched as it chased a snowshoe hare through the black spruce. It managed an amazing burst of speed and very nearly caught up to the hare. But when pressed the hare showed he is even quicker So, I was a bit surprised to look out the window and see the marten tugging and pulling at a hare it had caught during the night. It pulled the hare into the deep snow where it could butcher its prey concealed from the prying eyes of other predator and scavengers. First the marten gnawed off the hares head and cached it in the wood pile. The next day it cached the hares front legs. Cindy and I watched as the solitary marten entertained itself by running an obstacle course around and through the wood pile then roll on its back in the snow.

Though half the snowshoe hare was still left I spent the next two days watching and waiting for it to reappear. But just like it appeared, it disappeared. A pair of gray jays began to work the hare carcass hauling if away piece by piece, stashing it among the black spruce boughs. A pair of ravens wanted their share but only stared. For ravens, of course, are very cautious, even fearing their own food. But ravens are keen spies and watched carefully where the gray jays cached their loads. A hawk owl made a lightning quick chase and near miss of one of the gray jays. And later, I saw it swoop quickly again in the vicinity of the snowshoe hare carcass. Thinking it might have caught the gray jay I approached with my camera and telephoto lens. But the hawk owl had not caught the jay, instead it stood on the snowshoe hare carcass tugging. From the thick spruce nearby I heard a second hawk owl calling. It was the begging call of a female. After several minutes of biting and pulling the hawk owl, presumably a male, managed to tear off a chunk of the hare. It flew to a spruce and was soon joined by the female who took the offering.

Though half the snowshoe hare was still left I spent the next two days watching and waiting for it to reappear. But just like it appeared, it disappeared. A pair of gray jays began to work the hare carcass hauling if away piece by piece, stashing it among the black spruce boughs. A pair of ravens wanted their share but only stared. For ravens, of course, are very cautious, even fearing their own food. But ravens are keen spies and watched carefully where the gray jays cached their loads. A hawk owl made a lightning quick chase and near miss of one of the gray jays. And later, I saw it swoop quickly again in the vicinity of the snowshoe hare carcass. Thinking it might have caught the gray jay I approached with my camera and telephoto lens. But the hawk owl had not caught the jay, instead it stood on the snowshoe hare carcass tugging. From the thick spruce nearby I heard a second hawk owl calling. It was the begging call of a female. After several minutes of biting and pulling the hawk owl, presumably a male, managed to tear off a chunk of the hare. It flew to a spruce and was soon joined by the female who took the offering.

Northern hawk owl continues the butchering process of the marten’s kill. Though It is true that a predator may not use all of its prey, nothing is wasted.

Northern hawk owl continues the butchering process of the marten’s kill. Though It is true that a predator may not use all of its prey, nothing is wasted.