HUNTING IN WINTER

From a perch in a stand of stunted black spruce, a well camouflaged immature northern goshawk stalks its prey. Their short, wide wings and long tail give it both speed and manoeuverability to pursue prey in the forest. No small bird or mammal is safe from a sudden ambush, but this winter the large accipiters key on snowshoe hares.

From a perch in a stand of stunted black spruce, a well camouflaged immature northern goshawk stalks its prey. Their short, wide wings and long tail give it both speed and manoeuverability to pursue prey in the forest. No small bird or mammal is safe from a sudden ambush, but this winter the large accipiters key on snowshoe hares.

The snowshoe hare has perfected the art of camouflage, but as an extra defense against the goshawks, they often use snow burrows. But the snowshoe hares’ best defense against the sudden attacks by goshawks is its nocturnal behavior.

The snowshoe hare has perfected the art of camouflage, but as an extra defense against the goshawks, they often use snow burrows. But the snowshoe hares’ best defense against the sudden attacks by goshawks is its nocturnal behavior.

An adult northern goshawk feeds on a snowshoe hare.

An adult northern goshawk feeds on a snowshoe hare.

As I photographed a snowshoe hare this immature northern goshawk suddenly appeared out of the blue shadows and killed my photo subject. She mantles her prey with powerful wings.

As I photographed a snowshoe hare this immature northern goshawk suddenly appeared out of the blue shadows and killed my photo subject. She mantles her prey with powerful wings.

Often northern goshawks show little fear of humans. When I approached it flew a few yards away but quickly returned to its prey. The goshawk fed for nearly an hour leaving only the feet, fur, guts, head and large bones.

Often northern goshawks show little fear of humans. When I approached it flew a few yards away but quickly returned to its prey. The goshawk fed for nearly an hour leaving only the feet, fur, guts, head and large bones.

While the snowshoe hare population is near its peak this year, their primary predators populations (northern goshawk, lynx, coyote and great horned owl) are also peaking. And this heavy predation will inevitably cause the next snowshoe hare population crash.

While the snowshoe hare population is near its peak this year, their primary predators populations (northern goshawk, lynx, coyote and great horned owl) are also peaking. And this heavy predation will inevitably cause the next snowshoe hare population crash.

ALONE WITH THE NORTHERN GOSHAWK

For months, over two nesting seasons I spent nearly every day in the company of northern goshawks. Slowly they would reveal their secret lives.

For months, over two nesting seasons I spent nearly every day in the company of northern goshawks. Slowly they would reveal their secret lives.

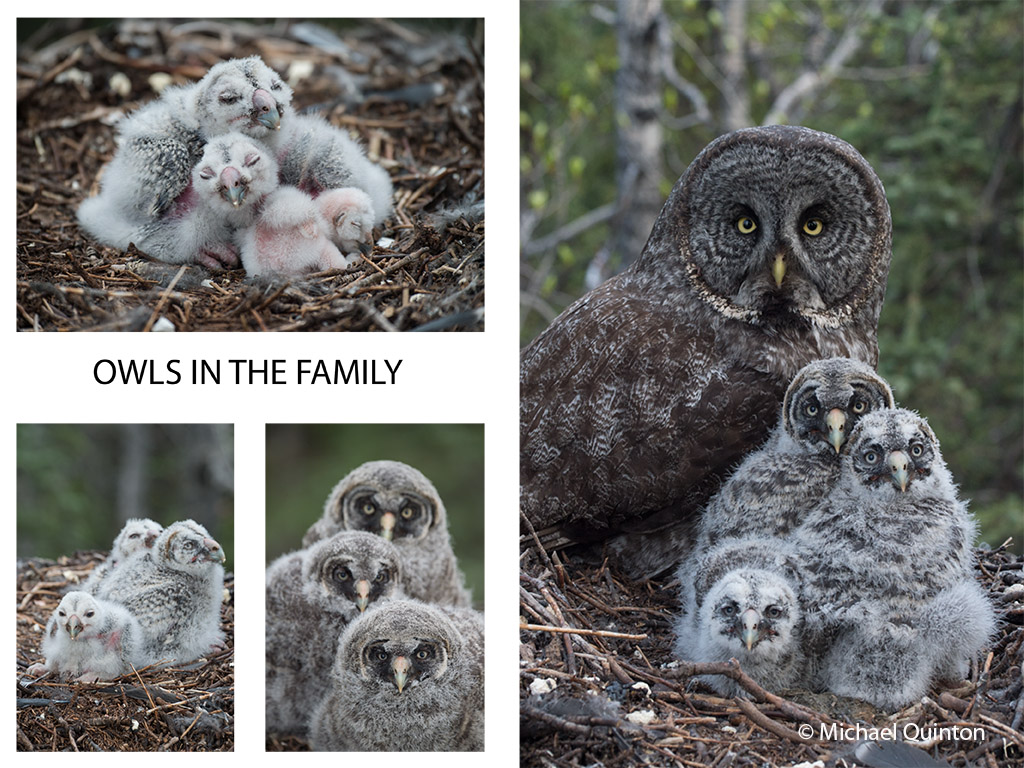

High in the canopy a female tends to her day old chicks.

High in the canopy a female tends to her day old chicks.

After the chicks hatch, northern goshawks become very aggressive at their nests. By visiting the nesting territory on a daily basis, starting early in the nesting season I seemed to have gained the trust of the goshawks. By building my blind near their nest under the cover of darkness, wearing the same clothes everyday and never disturbing the nest, I was able to climb into my photo blind or walk around the forest below unmolested.

SQUIRREL SMARTS

The great female goshawk rose up from her eggs and stepped to the edge of her three-foot wide nest. Eyes of blood locked onto her target. Diving headfirst off the nest, she pumped her wings quickly accelerating to attack speed. Long tail feathers flared and pivot, sending the goshawk speeding around the base of a large douglas fir and crashing into the understory. Squealing in terror, a red squirrel jumped to the trunk and instinctively darted to the opposite side, sticking like velcro to the rough, dry bark, then squirrel shot up the trunk into the canopy. Again the goshawk attacked. Going up, the squirrel was faster but on the way back down the goshawk closed the distance.

Among the thick branches of the canopy the squirrel had the edge, but not by much. Using feet, bill and wings, the goshawk literally swam through the boughs. Desperate to lose the hawk, the squirrel spiraled up the nest tree and right over those precious eggs, before jumping to an adjacent tree. The squirrel somehow missed being snagged by those talons, utilizing unearthly tricks of speed and anti-gravity. I could keep track of the chase through the various observation and lens slits cut into the photo blind, but the action was much too quick and hard to follow so I missed getting any photos. It was inevitable I guess, when I felt the squirrel coming up my blind tree, the gos riding his wind. A vision of the squirrel taking refuge up my pant leg was suddenly a painful possibility. Just as the squirrel shot inside the blind I yelled and smacked the side of the blind. Luck was cheap that June morning. After a couple of quick laps around the legs of me and my tripod, the squirrel dashed back out and jumped to the next tree about five feet away.

Slamming through the branches with little regard for its plumage, the gos didn’t let up. But the squirrel had a little luck of his own stashed away. Running headfirst down the trunk, the squirrel made an Olympic jump 25 feet from the ground. Bouncing off the forest floor the squirrel made for thicker scenery. After orbiting several more big trees and an amazing sling-shot the squirrel made it to a thick jungle of downfall. For the next 30 minutes, the goshawk perched 20 feet below her nest and preened. The squirrel barked, chattered and buzzed and told the world what he thought of goshawks nesting in his five acres.

Slamming through the branches with little regard for its plumage, the gos didn’t let up. But the squirrel had a little luck of his own stashed away. Running headfirst down the trunk, the squirrel made an Olympic jump 25 feet from the ground. Bouncing off the forest floor the squirrel made for thicker scenery. After orbiting several more big trees and an amazing sling-shot the squirrel made it to a thick jungle of downfall. For the next 30 minutes, the goshawk perched 20 feet below her nest and preened. The squirrel barked, chattered and buzzed and told the world what he thought of goshawks nesting in his five acres.

Three weeks earlier, the goshawk had calmly sat on her eggs while this same squirrel climbed the nest tree, dug into the bottom of the nest to find and nibble on mushrooms. I guess it seemed like the perfect place to dry mushrooms.

Three weeks earlier, the goshawk had calmly sat on her eggs while this same squirrel climbed the nest tree, dug into the bottom of the nest to find and nibble on mushrooms. I guess it seemed like the perfect place to dry mushrooms.

Unlike most species of gulls, Bonapart’s gulls nest in trees.

Unlike most species of gulls, Bonapart’s gulls nest in trees.

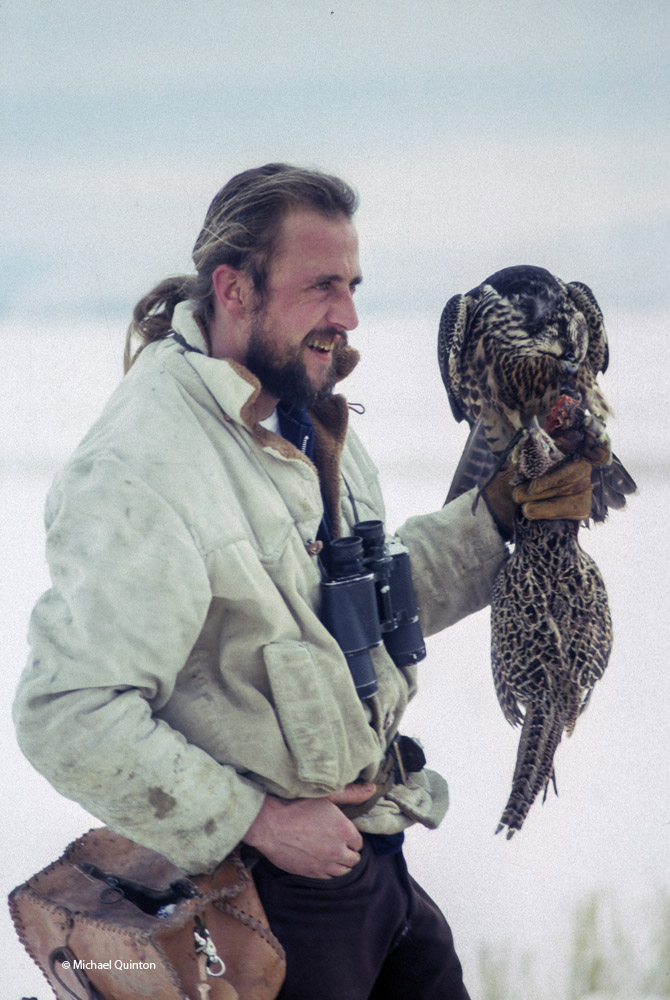

Week-old prairie falcons huddle together on a simple scrape at their cliff eyrie. The aggressive divebombing adults give Terry a glimpse into the potential flight characteristics of the young falcons.

Week-old prairie falcons huddle together on a simple scrape at their cliff eyrie. The aggressive divebombing adults give Terry a glimpse into the potential flight characteristics of the young falcons. Early in her training, (above) the young female prairie falcon is content to sit on the sidelines and let Terry demonstrate. From such modest beginnings, the prairie quickly responds to training and will be introduced to wild pheasants and ducks soon. (below)

Early in her training, (above) the young female prairie falcon is content to sit on the sidelines and let Terry demonstrate. From such modest beginnings, the prairie quickly responds to training and will be introduced to wild pheasants and ducks soon. (below) Casting off…

Casting off…

Another mallard for the bag. Every flight of Angel, the peregrine, was stunning,

Another mallard for the bag. Every flight of Angel, the peregrine, was stunning,

A falcon with a full crop is difficult to coax to the glove. Candy (right) was a fixture on the hunting trips. But once, after hawking for pheasants, Candy went missing and didn’t return to the car. Before leaving Terry threw out his coat. The next morning there she lay, waiting.

A falcon with a full crop is difficult to coax to the glove. Candy (right) was a fixture on the hunting trips. But once, after hawking for pheasants, Candy went missing and didn’t return to the car. Before leaving Terry threw out his coat. The next morning there she lay, waiting. Searching for suitable quarry for the falcons led us out to the edge of the lava flows of eastern Idaho. Passing a pair of ravens hanging out along the road, Terry slows and pulls over a couple of hundred yards down the road. Stepping out of the van Terry removes the peregrines hood and lifts the falcon above his head. In an instant, the peregrine is off the glove and power-pumping those long, slender wings into the wind towards the dumb-struck ravens. From a jump start, the ravens took flight and started to climb. Now, these ravens share the sky with all kinds of raptors from goshawks to golden eagles so the sudden appearance of a peregrine is no big deal. But this one had them in the crosshairs! Though the peregrine’s power of flight is legendary, she could not outclimb the ravens. A peregrines advantage is on the way back down and the ravens knew it. The flight was quickly a quarter mile above the sage highlands and climbing. But the persistent peregrine wouldn’t give up. As the flight threatened to disappear, out came the lure.

Searching for suitable quarry for the falcons led us out to the edge of the lava flows of eastern Idaho. Passing a pair of ravens hanging out along the road, Terry slows and pulls over a couple of hundred yards down the road. Stepping out of the van Terry removes the peregrines hood and lifts the falcon above his head. In an instant, the peregrine is off the glove and power-pumping those long, slender wings into the wind towards the dumb-struck ravens. From a jump start, the ravens took flight and started to climb. Now, these ravens share the sky with all kinds of raptors from goshawks to golden eagles so the sudden appearance of a peregrine is no big deal. But this one had them in the crosshairs! Though the peregrine’s power of flight is legendary, she could not outclimb the ravens. A peregrines advantage is on the way back down and the ravens knew it. The flight was quickly a quarter mile above the sage highlands and climbing. But the persistent peregrine wouldn’t give up. As the flight threatened to disappear, out came the lure. Desperate to get back to open water, the mallard deploys futile last-second maneuvers. The peregrines focus is clear. Mine, not so much.

Desperate to get back to open water, the mallard deploys futile last-second maneuvers. The peregrines focus is clear. Mine, not so much.

After a couple weeks of rainy weather I arrive at the camera station with a dry Nikon. The set-up is prone to problems. False triggers, battery failure, flash and sensor failure due to moisture, even snowshoe hares chewing cords. The beavers were busy refurbishing an old bare-bones lodge downstream and had all but stopped coming to the scent mound. But I kept the camera station operating. I like unexpected surprises.

After a couple weeks of rainy weather I arrive at the camera station with a dry Nikon. The set-up is prone to problems. False triggers, battery failure, flash and sensor failure due to moisture, even snowshoe hares chewing cords. The beavers were busy refurbishing an old bare-bones lodge downstream and had all but stopped coming to the scent mound. But I kept the camera station operating. I like unexpected surprises.