Several species of grouse inhabit my backyard (Wrangell/St. Elias National Park and Preserve), Alaska. Above, sharp-tailed grouse.

video link below: Grouse in my backyard

Several species of grouse inhabit my backyard (Wrangell/St. Elias National Park and Preserve), Alaska. Above, sharp-tailed grouse.

video link below: Grouse in my backyard

Check out my owl photos in June/July 2025 RANGER RICK by clicking link below.

Unlike most species of gulls, Bonapart’s gulls nest in trees.

Unlike most species of gulls, Bonapart’s gulls nest in trees.

Baby Bonapart’s gulls stayed in the nest for a day before jumping out and heading for nearby boreal ponds.

The aggressive and noisy Bonaparte’s gulls emit ear-splitting screams and drop hot, slimy poop bombs as they drive away enemies from their eggs and young, leaving enemies from ravens to eagles to nosy photographers diving for cover.

Bonaparte’s gull attacks!

To view video of Bonaparte’s gull click the link below.

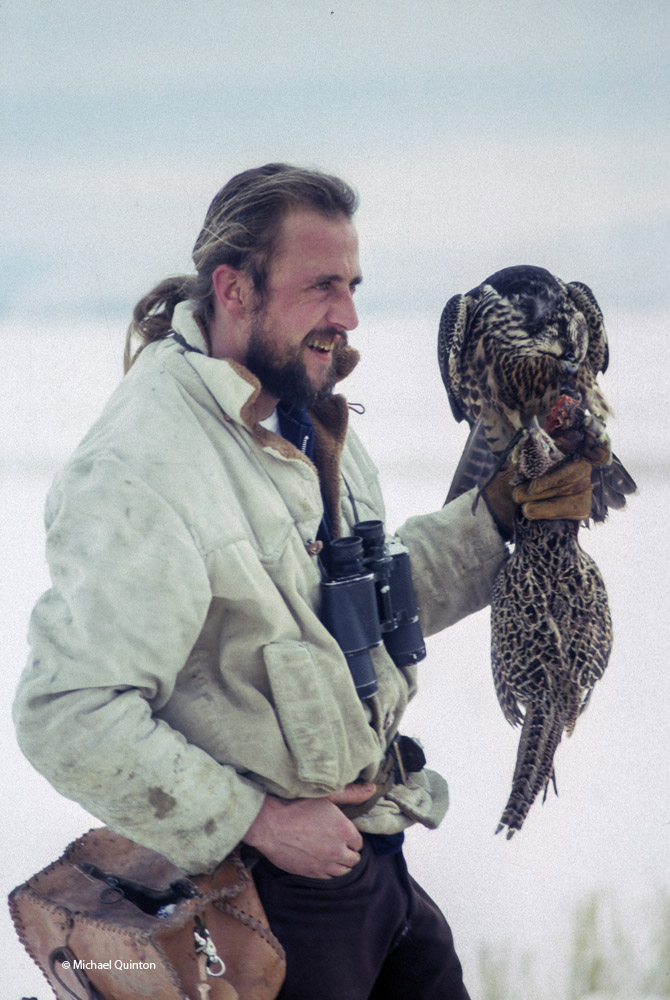

I couldn’t help but notice two hooded falcons perched on the back seat of a VW bug in the grocery store parking lot where I worked. ( forty-five years ago!) A guy with a ponytail drove it. When I said something about the prairie falcons, he looked a bit surprised. I guess nobody had ever correctly identified his falcons before. That’s how I first met Terry Heath. And with that introduction, we shared a short conservation that ended with Terry inviting me to photograph his hunting falcons. As I tagged along on hunting trips It became clear that for Terry, falconry was no hobby, nor was it just a sport hunting venture. No, Terry was in the grip of a full-blown obsession with falcons.

I couldn’t help but notice two hooded falcons perched on the back seat of a VW bug in the grocery store parking lot where I worked. ( forty-five years ago!) A guy with a ponytail drove it. When I said something about the prairie falcons, he looked a bit surprised. I guess nobody had ever correctly identified his falcons before. That’s how I first met Terry Heath. And with that introduction, we shared a short conservation that ended with Terry inviting me to photograph his hunting falcons. As I tagged along on hunting trips It became clear that for Terry, falconry was no hobby, nor was it just a sport hunting venture. No, Terry was in the grip of a full-blown obsession with falcons.

THE PRAIRIE FALCON

Week-old prairie falcons huddle together on a simple scrape at their cliff eyrie. The aggressive divebombing adults give Terry a glimpse into the potential flight characteristics of the young falcons.

Week-old prairie falcons huddle together on a simple scrape at their cliff eyrie. The aggressive divebombing adults give Terry a glimpse into the potential flight characteristics of the young falcons.

Early in her training, (above) the young female prairie falcon is content to sit on the sidelines and let Terry demonstrate. From such modest beginnings, the prairie quickly responds to training and will be introduced to wild pheasants and ducks soon. (below)

Early in her training, (above) the young female prairie falcon is content to sit on the sidelines and let Terry demonstrate. From such modest beginnings, the prairie quickly responds to training and will be introduced to wild pheasants and ducks soon. (below)

Casting off…

Casting off…

A PEREGRINE NAMED ANGEL

Another mallard for the bag. Every flight of Angel, the peregrine, was stunning,

Another mallard for the bag. Every flight of Angel, the peregrine, was stunning,

Angel suddenly reappears out of nowhere to stoop on the lure. (above) For a few worrying minutes, Angel was nowhere to be seen. Had she made a kill out of sight? A big worry.

Angel suddenly reappears out of nowhere to stoop on the lure. (above) For a few worrying minutes, Angel was nowhere to be seen. Had she made a kill out of sight? A big worry.  A falcon with a full crop is difficult to coax to the glove. Candy (right) was a fixture on the hunting trips. But once, after hawking for pheasants, Candy went missing and didn’t return to the car. Before leaving Terry threw out his coat. The next morning there she lay, waiting.

A falcon with a full crop is difficult to coax to the glove. Candy (right) was a fixture on the hunting trips. But once, after hawking for pheasants, Candy went missing and didn’t return to the car. Before leaving Terry threw out his coat. The next morning there she lay, waiting.

Searching for suitable quarry for the falcons led us out to the edge of the lava flows of eastern Idaho. Passing a pair of ravens hanging out along the road, Terry slows and pulls over a couple of hundred yards down the road. Stepping out of the van Terry removes the peregrines hood and lifts the falcon above his head. In an instant, the peregrine is off the glove and power-pumping those long, slender wings into the wind towards the dumb-struck ravens. From a jump start, the ravens took flight and started to climb. Now, these ravens share the sky with all kinds of raptors from goshawks to golden eagles so the sudden appearance of a peregrine is no big deal. But this one had them in the crosshairs! Though the peregrine’s power of flight is legendary, she could not outclimb the ravens. A peregrines advantage is on the way back down and the ravens knew it. The flight was quickly a quarter mile above the sage highlands and climbing. But the persistent peregrine wouldn’t give up. As the flight threatened to disappear, out came the lure.

Searching for suitable quarry for the falcons led us out to the edge of the lava flows of eastern Idaho. Passing a pair of ravens hanging out along the road, Terry slows and pulls over a couple of hundred yards down the road. Stepping out of the van Terry removes the peregrines hood and lifts the falcon above his head. In an instant, the peregrine is off the glove and power-pumping those long, slender wings into the wind towards the dumb-struck ravens. From a jump start, the ravens took flight and started to climb. Now, these ravens share the sky with all kinds of raptors from goshawks to golden eagles so the sudden appearance of a peregrine is no big deal. But this one had them in the crosshairs! Though the peregrine’s power of flight is legendary, she could not outclimb the ravens. A peregrines advantage is on the way back down and the ravens knew it. The flight was quickly a quarter mile above the sage highlands and climbing. But the persistent peregrine wouldn’t give up. As the flight threatened to disappear, out came the lure.

Desperate to get back to open water, the mallard deploys futile last-second maneuvers. The peregrines focus is clear. Mine, not so much.

Desperate to get back to open water, the mallard deploys futile last-second maneuvers. The peregrines focus is clear. Mine, not so much.

A pair of gray jays have finished their nest by early April.

A pair of gray jays have finished their nest by early April.

I first saw the gray jays as they flew across the road in front of me. They both carried loads of building materials in their bills. The next day I went searching for their nest. It was rather easy to find as they were both busy with construction. The nest was about twenty feet high in a medium-sized black spruce. They had completed a loose bowl of dry spruce twigs and were currently engaged with stuffing this framework with insulation. The pair gathered black, grizzly hair lichens as well as spruce grouse feathers. But their most prized finds were the long soft plumes of the northern hawk owl. After delivering a load of insulation, the birds would hop into the nest and push with bills and feet as they rotated around in the nest, fitting and forming it to just the right shape. The female begins sitting on the nest and a week later her clutch of spotted eggs is complete. The pair is quiet at the nest site and does not attract attention of those nest raiders, magpies and ravens. When a red squirrel was spotted nearby it was dive-bombed by the male gray jay and driven away.

The female begins sitting on the nest and a week later her clutch of spotted eggs is complete. The pair is quiet at the nest site and does not attract attention of those nest raiders, magpies and ravens. When a red squirrel was spotted nearby it was dive-bombed by the male gray jay and driven away.

For nearly three weeks the female incubated her four eggs. A few times a day she will leave the nest but only for a few minutes, perhaps to drink.

For nearly three weeks the female incubated her four eggs. A few times a day she will leave the nest but only for a few minutes, perhaps to drink.

The male gray jay shows up at the nest about once an hour or so to feed his mate.

The male gray jay shows up at the nest about once an hour or so to feed his mate.

Laying eggs is an energy drain and the female spends hours sleeping.

Laying eggs is an energy drain and the female spends hours sleeping.

Early nesting grays jays must be able to handle cold, wet conditions in their Alaskan habitat.

Early nesting grays jays must be able to handle cold, wet conditions in their Alaskan habitat.

Both adults help feed the quickly growing gray jay chicks. Gray jays store amazing amounts of food including carrion and I wondered if they would feed their cached supplies to their chicks. But Instead they foraged the ground for insects and larva, much better food for the new chicks.

Both adults help feed the quickly growing gray jay chicks. Gray jays store amazing amounts of food including carrion and I wondered if they would feed their cached supplies to their chicks. But Instead they foraged the ground for insects and larva, much better food for the new chicks.

As the chicks grew the gray jays cached stores of carrion became more important. And it quickly became apparent that the nest would never hold four growing chicks for long. By the time the chicks were about two weeks old, they jostle for the best position at the nest. I witnessed deliberate attempts by the larger chicks to force their smaller siblings out. One morning there were just two chicks left in the nest. Below the nest on the ground were the missing chicks, both dead. From human eyes, a tragic event. But for nature, another one of those mysteries of survival.

As the chicks grew the gray jays cached stores of carrion became more important. And it quickly became apparent that the nest would never hold four growing chicks for long. By the time the chicks were about two weeks old, they jostle for the best position at the nest. I witnessed deliberate attempts by the larger chicks to force their smaller siblings out. One morning there were just two chicks left in the nest. Below the nest on the ground were the missing chicks, both dead. From human eyes, a tragic event. But for nature, another one of those mysteries of survival.

Come July of this year the name of the gray jay will change once again. They will officially be known as the Canada jay. And like camp robber and whiskey jack, gray jay will be just another nickname used to describe this gray-colored jay of the northern forests.

From a perch in a stand of stunted black spruce, a well camouflaged immature northern goshawk stalks its prey. Their short, wide wings and long tail give it both speed and manoeuverability to pursue prey in the forest. No small bird or mammal is safe from a sudden ambush, but this winter the large accipiters key on snowshoe hares.

From a perch in a stand of stunted black spruce, a well camouflaged immature northern goshawk stalks its prey. Their short, wide wings and long tail give it both speed and manoeuverability to pursue prey in the forest. No small bird or mammal is safe from a sudden ambush, but this winter the large accipiters key on snowshoe hares.

The snowshoe hare has perfected the art of camouflage, but as an extra defense against the goshawks, they often use snow burrows. But the snowshoe hares’ best defense against the sudden attacks by goshawks is its nocturnal behavior.

The snowshoe hare has perfected the art of camouflage, but as an extra defense against the goshawks, they often use snow burrows. But the snowshoe hares’ best defense against the sudden attacks by goshawks is its nocturnal behavior.

An adult northern goshawk feeds on a snowshoe hare.

An adult northern goshawk feeds on a snowshoe hare.

As I photographed a snowshoe hare this immature northern goshawk suddenly appeared out of the blue shadows and killed my photo subject. She mantles her prey with powerful wings.

As I photographed a snowshoe hare this immature northern goshawk suddenly appeared out of the blue shadows and killed my photo subject. She mantles her prey with powerful wings.

Often northern goshawks show little fear of humans. When I approached it flew a few yards away but quickly returned to its prey. The goshawk fed for nearly an hour leaving only the feet, fur, guts, head and large bones.

Often northern goshawks show little fear of humans. When I approached it flew a few yards away but quickly returned to its prey. The goshawk fed for nearly an hour leaving only the feet, fur, guts, head and large bones.

While the snowshoe hare population is near its peak this year, their primary predators populations (northern goshawk, lynx, coyote and great horned owl) are also peaking. And this heavy predation will inevitably cause the next snowshoe hare population crash.

While the snowshoe hare population is near its peak this year, their primary predators populations (northern goshawk, lynx, coyote and great horned owl) are also peaking. And this heavy predation will inevitably cause the next snowshoe hare population crash.

For months, over two nesting seasons I spent nearly every day in the company of northern goshawks. Slowly they would reveal their secret lives.

For months, over two nesting seasons I spent nearly every day in the company of northern goshawks. Slowly they would reveal their secret lives.

High in the canopy a female tends to her day old chicks.

High in the canopy a female tends to her day old chicks.

After the chicks hatch, northern goshawks become very aggressive at their nests. By visiting the nesting territory on a daily basis, starting early in the nesting season I seemed to have gained the trust of the goshawks. By building my blind near their nest under the cover of darkness, wearing the same clothes everyday and never disturbing the nest, I was able to climb into my photo blind or walk around the forest below unmolested.

The great female goshawk rose up from her eggs and stepped to the edge of her three-foot wide nest. Eyes of blood locked onto her target. Diving headfirst off the nest, she pumped her wings quickly accelerating to attack speed. Long tail feathers flared and pivot, sending the goshawk speeding around the base of a large douglas fir and crashing into the understory. Squealing in terror, a red squirrel jumped to the trunk and instinctively darted to the opposite side, sticking like velcro to the rough, dry bark, then squirrel shot up the trunk into the canopy. Again the goshawk attacked. Going up, the squirrel was faster but on the way back down the goshawk closed the distance.

Among the thick branches of the canopy the squirrel had the edge, but not by much. Using feet, bill and wings, the goshawk literally swam through the boughs. Desperate to lose the hawk, the squirrel spiraled up the nest tree and right over those precious eggs, before jumping to an adjacent tree. The squirrel somehow missed being snagged by those talons, utilizing unearthly tricks of speed and anti-gravity. I could keep track of the chase through the various observation and lens slits cut into the photo blind, but the action was much too quick and hard to follow so I missed getting any photos. It was inevitable I guess, when I felt the squirrel coming up my blind tree, the gos riding his wind. A vision of the squirrel taking refuge up my pant leg was suddenly a painful possibility. Just as the squirrel shot inside the blind I yelled and smacked the side of the blind. Luck was cheap that June morning. After a couple of quick laps around the legs of me and my tripod, the squirrel dashed back out and jumped to the next tree about five feet away.

Slamming through the branches with little regard for its plumage, the gos didn’t let up. But the squirrel had a little luck of his own stashed away. Running headfirst down the trunk, the squirrel made an Olympic jump 25 feet from the ground. Bouncing off the forest floor the squirrel made for thicker scenery. After orbiting several more big trees and an amazing sling-shot the squirrel made it to a thick jungle of downfall. For the next 30 minutes, the goshawk perched 20 feet below her nest and preened. The squirrel barked, chattered and buzzed and told the world what he thought of goshawks nesting in his five acres.

Slamming through the branches with little regard for its plumage, the gos didn’t let up. But the squirrel had a little luck of his own stashed away. Running headfirst down the trunk, the squirrel made an Olympic jump 25 feet from the ground. Bouncing off the forest floor the squirrel made for thicker scenery. After orbiting several more big trees and an amazing sling-shot the squirrel made it to a thick jungle of downfall. For the next 30 minutes, the goshawk perched 20 feet below her nest and preened. The squirrel barked, chattered and buzzed and told the world what he thought of goshawks nesting in his five acres.

Three weeks earlier, the goshawk had calmly sat on her eggs while this same squirrel climbed the nest tree, dug into the bottom of the nest to find and nibble on mushrooms. I guess it seemed like the perfect place to dry mushrooms.

Three weeks earlier, the goshawk had calmly sat on her eggs while this same squirrel climbed the nest tree, dug into the bottom of the nest to find and nibble on mushrooms. I guess it seemed like the perfect place to dry mushrooms.

A pair of northern hawk owls check out the view from atop a prospective nesting cavity. Hawk owls, like other owls, do not build a nest but use natural cavities and bowled out snags. The male establishes a territory that includes potential nests sites, but it seems to be the female who makes the final choice of snags.

After settling on another snag, the female incubates her eggs. Hawk owls nest early, usually in late April and will endure winter conditions.

Check out my photo story about northern hawk owls in the May 2018 issue of RANGER RICK, Just click the link below.

At nearly four weeks a fledged great gray owlet has jumped from its nest to the forest floor. Free from the confines of the nest, (I too am finally freed from the solitary confinement of my photo blind) the owlet walks and leaps to a place to perch.

At nearly four weeks a fledged great gray owlet has jumped from its nest to the forest floor. Free from the confines of the nest, (I too am finally freed from the solitary confinement of my photo blind) the owlet walks and leaps to a place to perch.

Fledged owlets move about fifty to a hundred feet every day, picking out a slanting tree to climb. The ground is a dangerous place for the young, flightless owls. The mobile owl family becomes more difficult to locate by the day.

Adults continue to care for their owlets. The female (above), usually staying near the owlets, will do some hunting when an opportunity presents itself.

Adults continue to care for their owlets. The female (above), usually staying near the owlets, will do some hunting when an opportunity presents itself.

The female with a young snowshoe hare delivered by her mate.

The female with a young snowshoe hare delivered by her mate.

The snowshoe hare, large prey for a great gray owl, will feed her and her owlets for a day. The prey is cached on the ground between feedings.

The snowshoe hare, large prey for a great gray owl, will feed her and her owlets for a day. The prey is cached on the ground between feedings.

Female perches on log after caching the snowshoe hare.

Female perches on log after caching the snowshoe hare.

Adult female drinking.

Regurgitated great gray owl pellets and white spruce cones on a bed of sphagnum moss below an owlets perch.

Regurgitated great gray owl pellets and white spruce cones on a bed of sphagnum moss below an owlets perch.

Female delivers her owlet a freshly caught red-backed vole. Fledged owlets swallow voles whole.

Female delivers her owlet a freshly caught red-backed vole. Fledged owlets swallow voles whole.

A tough job but it must be done.

A tough job but it must be done.

Female great gray owl holds another red-backed vole just delivered by her mate. The well fed owlets are not hungry at the moment so the vole will be placed in the nest for later. For nearly four weeks I had a rare and intimate view of the owls family life at the nest.

As the female raises up from her brooding, she gives me my first look at the tiny owlets.

As the female raises up from her brooding, she gives me my first look at the tiny owlets.

The owlets hatching over a period of about a week account for their age and size difference. Competition among the owls for food favors the older owlets. The smallest owlet, here just a couple of days old, could not hold its own and one morning it was gone.

The owlets hatching over a period of about a week account for their age and size difference. Competition among the owls for food favors the older owlets. The smallest owlet, here just a couple of days old, could not hold its own and one morning it was gone.

https://youtu.be/gG-pWZZjKt4

Watch video of male delivering a red-backed vole. (above)

After a couple of weeks there is no longer a need for constant brooding and the female finally gets a little time to herself. But even then she stays close and alert for danger. One day a pair of ravens hung around the nest in an attempt to harass her from the nest long enough to steal a chick. She held tight and her mate arrived to chase the ravens about. Eventually the ravens left.

As the female perched near the nest her mate arrives with prey and she follows him in.

As the female perched near the nest her mate arrives with prey and she follows him in.

Arriving at the nest the female takes possession of the red-backed vole from her mate. (right) After a brief pause at the nest the male is off again to continue hunting. (below)

Visit next week for the final post in this series, SECRET LIFE OF A FOREST HUNTER-PART THREE