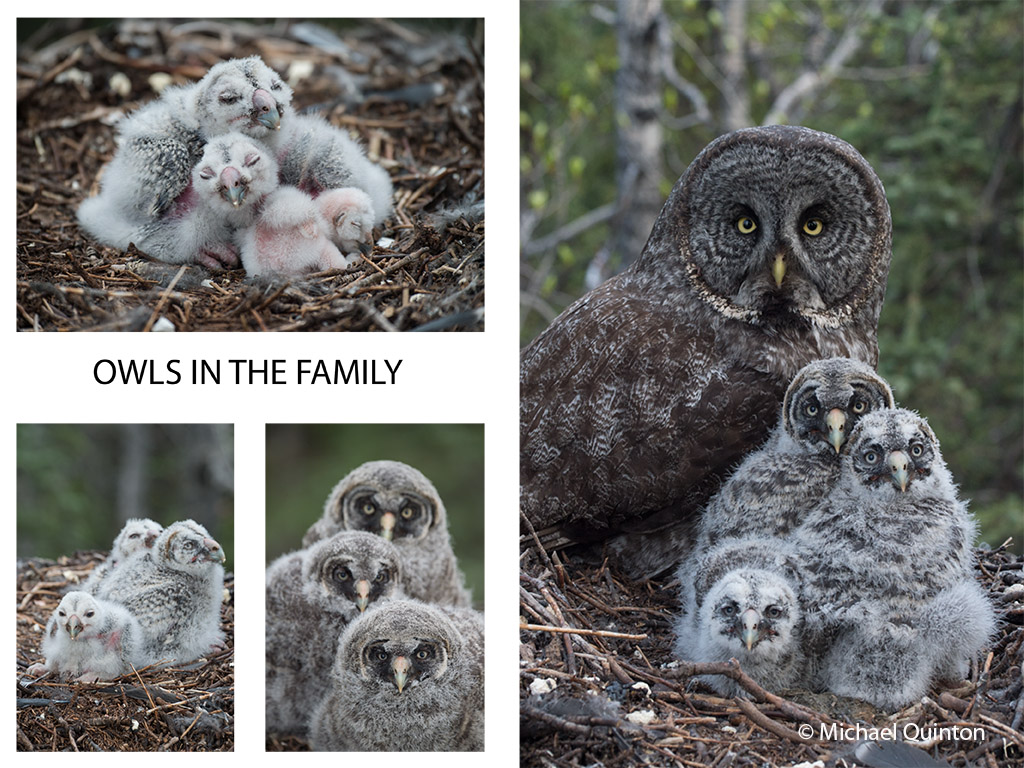

A female great gray owl spreads her wings as she gently lands on the edge of her nest to resume incubating her four eggs. For two months this nest is the nucleus of activity for a pair of great gray owls. Owls do not build their own nests. Instead they use a variety of ready-made and vacant nests, like this one built many years before by northern goshawks. The great grays I had photographed three decades ago in Idaho prefered the bowled out tops of large broken pine trees for their nests.

A female great gray owl spreads her wings as she gently lands on the edge of her nest to resume incubating her four eggs. For two months this nest is the nucleus of activity for a pair of great gray owls. Owls do not build their own nests. Instead they use a variety of ready-made and vacant nests, like this one built many years before by northern goshawks. The great grays I had photographed three decades ago in Idaho prefered the bowled out tops of large broken pine trees for their nests.

Eggs laid in the third week of April must be protected from the weather, as incubation begins with the first egg. The female does all the incubating and will sit on her eggs for thirty days.

Eggs laid in the third week of April must be protected from the weather, as incubation begins with the first egg. The female does all the incubating and will sit on her eggs for thirty days.

To gain access to the nesting great grays, more than fifty feet above the forest floor, I scabbed two long extensions ladders together and added an additional extension using two by fours. I had located the nest thirteen years ago. The three-foot wide nest was built by northern goshawks in a towering quaking aspen. Every spring I’d hike to the remote nest site to check its status. Goshawks had used the nest only once during the last thirteen years.

To gain access to the nesting great grays, more than fifty feet above the forest floor, I scabbed two long extensions ladders together and added an additional extension using two by fours. I had located the nest thirteen years ago. The three-foot wide nest was built by northern goshawks in a towering quaking aspen. Every spring I’d hike to the remote nest site to check its status. Goshawks had used the nest only once during the last thirteen years.

From my self-imposed confinement in the lofty, swaying photo blind, I witnessed much more than just the daily activities of the great gray owls. The female owl and I watched red squirrels, that rarely seen red squirrel predator, the marten, groups of migrating caribou, and a variety of bird life. Early one morning, not long after arriving, a huffing grizzly bear sow and yearling cub who had caught my scent quickly moved off beneath the blind. Once a curious cow moose who could hear my camera clicking finally looked up.

A couple of times a day the female flies off the nest to drink, cast her pellet and perhaps stretch before returning to her precious clutch of eggs.

A couple of times a day the female flies off the nest to drink, cast her pellet and perhaps stretch before returning to her precious clutch of eggs.

The male hunts for his mate and has just arrived with prey, a baby red squirrel. The male, who hunts during the day using sight and sound, is an opportunist and preys on a variety of small birds and mammals. Red-backed voles are by far the most important prey but shrews, small birds, and young snowshoe hares are also prey. Adult red squirrels are usually too alert and quick to be given much attention by the hunting male. But young squirrels, probably raided from their grass and sphagnum nests, are regularly on the menu.

The male hunts for his mate and has just arrived with prey, a baby red squirrel. The male, who hunts during the day using sight and sound, is an opportunist and preys on a variety of small birds and mammals. Red-backed voles are by far the most important prey but shrews, small birds, and young snowshoe hares are also prey. Adult red squirrels are usually too alert and quick to be given much attention by the hunting male. But young squirrels, probably raided from their grass and sphagnum nests, are regularly on the menu.